|

|

Friday, September 28, 2007.

Paris, France

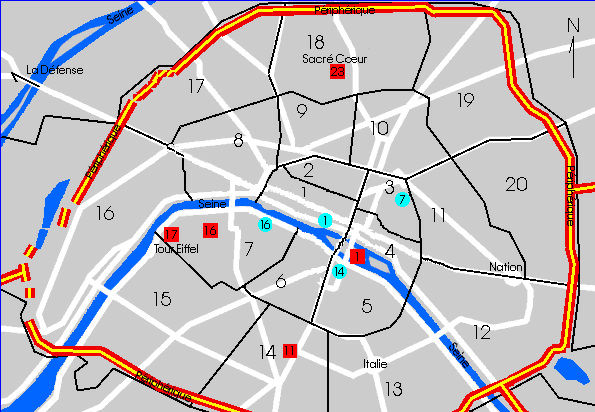

The Musée de l'Armée (Red Square 16 on the map) is a museum at Les Invalides in Paris, France.

Les Invalides was built as a hospital and home for disabled soldiers by Louis XIV.

It now houses the Tomb of Napoleon and the museum of the Army of France. The

museum's collections cover the time period from the middle ages until the 20th century.

Sadly for me, the portion of the Army museum I am most interested in - the

Napoleonic ear - was closed for renovation.

|

|

|

|

My original plan for today was to go to Versailles. I got on a train that got halfway there and then

the RER train stopped. Another passenger figured out even though the displayed destination seemed

correct, it just wasn't going on to Versailles. By the time I got things straight I missed

the opening time of the palace. Because I want to try for pictures of the Hall of Mirrors

without any tourists in it, I will try Versailles another day. Giving in, I turned around

in this RER station (above) and

headed back towards the Seine. Note that there are computer screens that show when

the next few trains are expected.

|

I got off the train and walked up to street level. Here is the Pont Alexandre III, or

Alexander III Bridge.

In October 1896, the first stone was laid by the Russian Tsar Nicolas II.

The bridge was named after his father, Tsar Alexander III. The Pont Alexandre III

opened just in time for the

Universal Exposition of 1900 (as was the d"Orsay railroad station).

|

|

|

I am getting closer and closer to the complex known as the Hôtel des Invalides.

It was founded in 1671 by Louis XIV, the Sun King. He wanted to provide accommodation

for disabled and impoverished war veterans. The building was completed in 1676

and housed up to 4,000 war veterans.

|

Here in one of the interior courtyards of the Hôtel des Invalides

- Cour d'Honneur (Court of Honor) -

is the entry to the Musée de l'Armée.

|

Suits of armor ...

|

Barding (also spelled bard or barb) is armor for horses. During the late Middle Ages as armor protection for knights became more effective, their mounts became targets. This tactic was effective for the English at the Battle of Crécy in the fourteenth century where archers shot horses and heavy infantry

killed the French knights after they dismounted. Barding developed as a response to such events.

Surviving period examples of barding are rare.

|

I believe this is a hauberk or short-sleeved mail shirt, made up of interlocking iron rings,

with an attached hood, or coif. That's a reflection of my camera peering out from

the face area.

|

At the opening of the Middle Ages swords tended to have blades just under a yard in

length with a grip designed to accommodate a single hand; the other hand being

concerned with the grip of a shield. Essentially all of the earliest medieval

swords and many throughout the period were designed to cut, having surprisingly

thin blades, especially towards the tip, which was often rounded. By the close

of the Middle Ages, swords increasingly are stouter and more sharply pointed,

being optimized for the thrust, the cut having been rendered less effective by

improvements in armor. Similarly, with these armor improvements, the shield

became redundant and swords with hilts effectively accommodating both hands

made their appearance and grew in popularity.

|

Medieval firearms.

The firearms at left with what looks like cord near the firing mechanism look to me like

matchlocks - the rest flintlocks. The matchlock secured a lighted wick in a moveable arm which, when the trigger was depressed, was brought down against the flash pan to ignite the powder.

An improvement, the flintlock was developed in France around 1612.

This mechanism worked by attaching the flint to a spring-loaded arm. When the trigger is

pressed, the cover slides off the flash pan, then the arm snaps forward striking the

flint against a metal plate over the flash pan and hopefully produces enough sparks to ignite the powder.

|

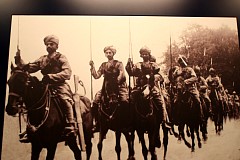

Just some interesting history and a picture.

|

I waited until someone walked by what I think is a medieval mortar and stone or cast

iron shot. This would have been used against solid targets like a castle. I picture

on the right is of the "handles" used to hoist a cannon onto its carriage. The original

"Love Handles"?

|

This gun was called the " French 75". Officially known as the 75 mm Field Gun, Model of 1897. Its innovative development was its recoil system consisting of two hydraulic cylinders,

a floating piston, a connected piston, a head of gas and a reservoir of oil. This made for a soft,

smooth operation.

|

A few photographs I found interesting. The way the poor man on the stretcher is being carried

lead me to believe he's dead - he is probably even in rigor mortis. On the picture on

the right, as the German prisoners stand stiffly at attention, look at the expression

of the French soldiers next to the officer with the open notebook and the intense French

officer at the German's side.

|

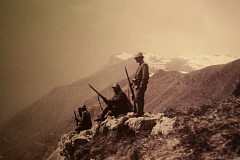

These rifles were modified for sniper use by soldiers so they could shoot from the

trenches without risking exposure.

|

A wheeled heavy machine gun and behind it a mortar.

|

A few more pictures. I would also like to stand here on this mountain and admire the view ...

|

Masks were taken from men with horrible war wounds. I recall that the majority of deaths and

injuries during World War I were caused by high explosive shell fired by artillery. It seems

to me that is what caused these wounds.

|

Attached to Les Invalides is

the Royal chapel, better known as the

Dôme des Invalides. This church with it's 107 meter high dome was for exclusive

use of the royal family. Construction of the dome was completed in 1708. Plans

to bury the remains of the Royal Family were set aside after the death of king

Louis XIV, and in 1840 Louis-Philippe repatriated the remains of the Emperor

Napoleon from St. Helena, where he was buried after his death 19 years earlier.

The Dôme des Invalides now also houses the tombs of several other military

leaders like Turenne, Vauban and marshall Foch.

|

At ground level you can peer down upon Napoleon I's sarcophagus.

|

Looking up you see the ornate underside of the dome.

|

Let's venture down this very dreary black marble staircase to reach the level of

Napoleon's sarcophagus. It's very dark, I had to lighten these photographs.

|

I had to lighten this photo. It's taken after descending the steps above

which get you to sarcophagus-level. One would have to set up exterior lighting

to get this shot. Rest easy, Mon général.

|